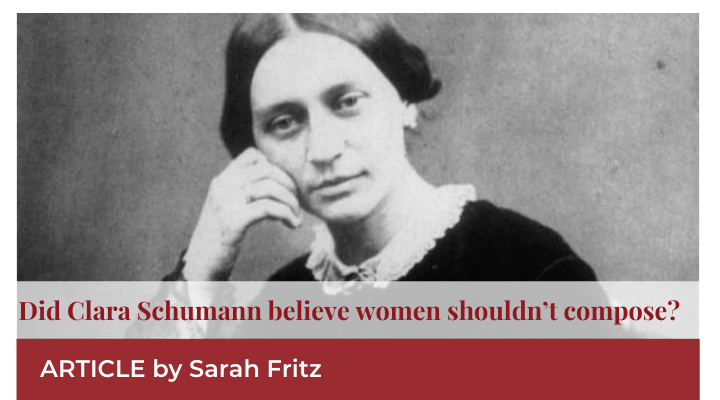

Did Clara Schumann believe women shouldn’t compose?

ARTICLE | 11 AUGUST, 2021

“There is nothing greater than the joy of composing.”

Clara Schumann

Twenty-year-old, Clara Schumann née Wieck’s quote, “A women must not desire to compose,” is among her most famous one-liners. Out of context, it implies that the reason Clara stopped composing was due to her gender. The decontextualization of such a harsh, painful statement from one of the most promising and well-educated women composers of the nineteenth century has caused unbridled rippling effects.

In a recent Twitter poll of over 150 responders, nearly forty percent said the quote had impacted them negatively, hurtfully. Though an equal number said they’d never heard the quote before, thankfully, only around ten percent answered it was empowering and motivating, and even fewer answered it affected them indifferently.

Composer Gabriela Ortiz, commissioned by the New York Philharmonic to write a work about Clara for a performance in March 2022, responded in a recent interview for La Jordana:

“Of course, we women can write. It has been a very complex process to achieve

gender equality and get to where we are. It has been quite a historical struggle.

However, we can write, and there is nothing to stop us.”

For most, Clara’s quote inspires a strong reaction. Composer Patricia Wallinga tweeted, “It makes me feel deep sympathy for Clara, and makes me want to ensure no other girls grow up thinking this.” Composer Elizabeth Gentner added, “The comment sits on an open wound for most of us,” but she also prefers to include an ellipsis, “…she must do it anyway.”

Given how impactful this popularized isolated quote has become, exposing its full context is overdue.

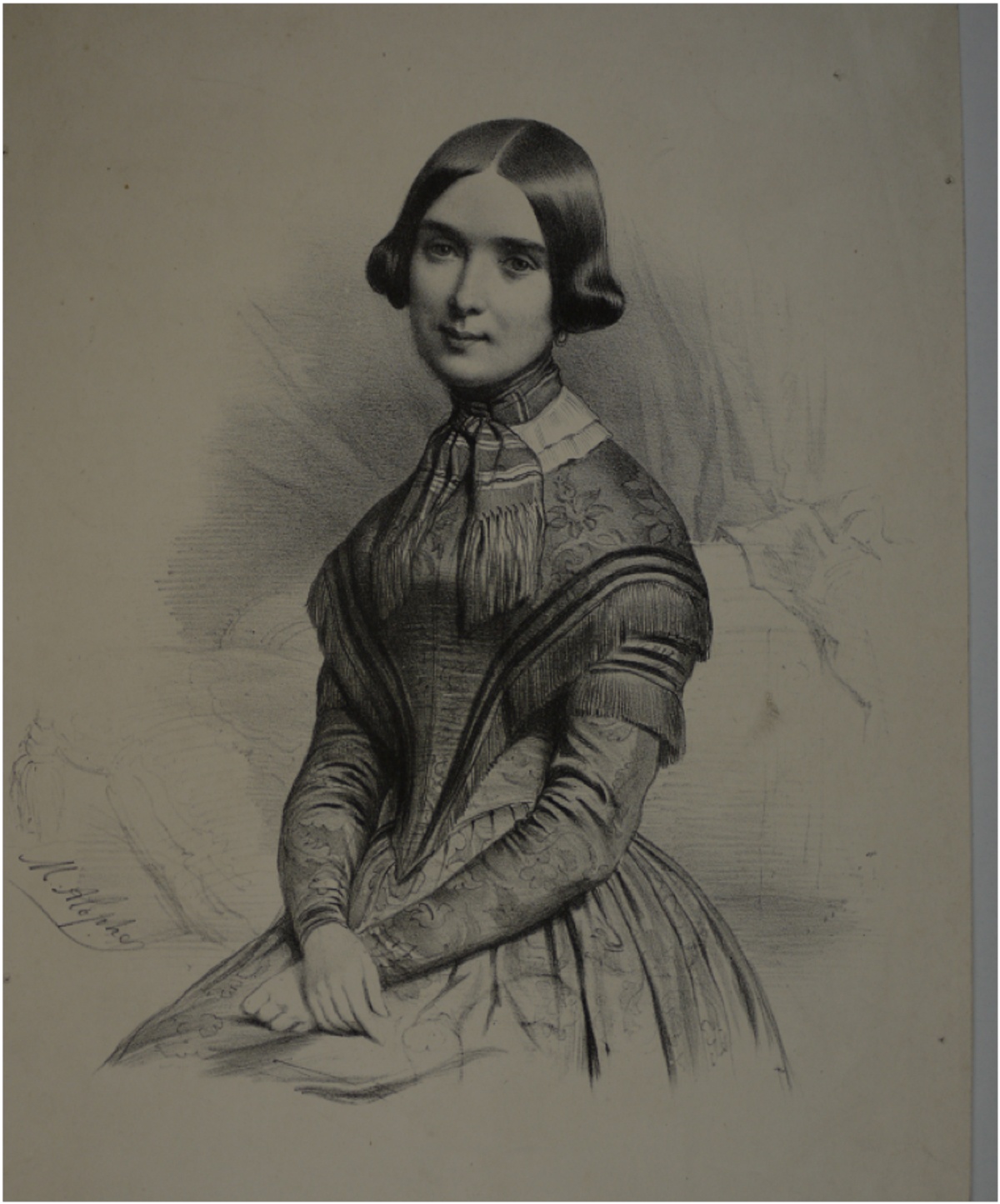

Clara Wieck (1819-1896), age 18, 1838 in Vienna

The true impetus for Clara’s harsh judgement of women in her diary turns its meaning upside down. Taken from the Berthold Litzmann biography of Clara Schumann published in 1902 (translation by Grace E. Hadow):

“The pianist Camilla Pleyel was celebrating great triumphs in Leipzig…

‘Everything that I read about her,’ says [Clara’s] diary ‘is an ever clearer proof that she is above me; and if this be so I can hardly fail to be completely downcast. I think that I shall submit to it in time, for indeed oblivion is the fate of every artist who is not creative. I once thought that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose—not one has been able to do it, and why should I expect to? It would be arrogance, though indeed, my Father led me into it in earlier days.’” [November, 1839]

Irony of ironies, Clara wrote the quote in response to a rivalry with another woman composer, Camilla (Marie) Pleyel.

Marie Pleyel (1811-1875) age 28 in 1839

Clara contradicts herself within the same diary entry, claiming Camilla is “proof she is above me” then undermining all women composers. Clara neglects to note, or is unaware of the fact that Camilla was eight years older than her. These inconsistencies betray the youthfulness of Clara’s vulnerable age of twenty. Though she’d already achieved an international renown as a formidable piano virtuosa, as a composer, she was struggling for confidence.

Other similarly contradictory statements appear in her letters around this time. In writing to her then fiancée in March 4th, 1838, she writes of her difficulty composing:

She realizes, even as she’s writing it, that to judge herself based on gender is a statement of self-doubt—or what today is termed imposter syndrome. Whenever Clara battled with insecurities about her work, she fell victim to the parroted misogynies of her time—that women shouldn’t compose.

Her recognition of these thoughts as self-doubt hints that she knew it wasn’t true. But this battle waged within her all her life. The inner struggle—were women supposed to compose or not?—plagued her and inhibited her work. Self-doubt echoes in almost all her diary entries about her composing.

But it didn’t stop her. Her desire to write music, no matter her turmoil, was irrepressible.She composed for another fifteen years after these writings. Her opuses 12 through 23 included some of her best works—her piano sonata, piano trio, dozens of lieder, piano romanzes, violin romanzes, a first movement of a second piano concerto, and more.

The works of other women composers, especially Fanny Hensel and Pauline Viardot, were in her high esteem. Though society told her she should “not desire to compose,” she never could suppress it or condemn other women for it. Her desire overpowered her self-doubt.

Clara’s passion for composition shines through in her diary on October 2nd, 1846. At age twenty-seven (already a mother of four), her confidence was growing. She writes:

“There is nothing greater than the joy of composing something oneself, and then listening to it.”

Amidst her extraordinary career, full of laurels and unparalleled success, her statement, “There is nothing greater than the joy of composing,” implies her love of writing music soared above her joy in performing.

She doesn’t say, but there are many possibilities.

The timing, 1855, intersects with the health decline and death of her husband. It’s possible her grief played a role in the end of her creations. French composer, Louise Farrenc also stopped composing when her daughter died.

Writing music as gifts for her husband had motivated almost half of Clara’s works during marriage. Without him, perhaps it simply hurt too much.

Composition also requires leisure time. American composer, Florence Price wrote that a painful injury became a boon for her creations, “When shall I ever be so fortunate again as to break a foot.” It enabled her the time to write some of her greatest orchestral works.

Clara Schumann, age 35 in 1854

At age thirty-six, Clara’s leisure time all but disappeared when she became a single parent. Under the strain of perpetual concert tours necessary to support her seven children, the luxury to compose fell on the sacrificial pile.

It cannot be discounted that Clara also met Johannes Brahms around this time. Josef Joachim also quit composing within a few years of meeting the man who would become one of the Three Bs. Maybe both Clara and Josef in comparing their work to Johannes judged themselves inadequate and chose to devote themselves to performing as a result.

In other words, Clara likely quit composing for many reasons, but because “a woman should not desire to compose” was not one of them. The misogynist adage pervaded 19th century culture, as in a pamphlet circulated in 1873 by Otto Gumprecht titled “Women in Music” which,

“Explains the lack of women in music as a natural outgrowth of women’s supposedly essential inability to handle challenging intellectual tasks such as music composition.” [Brahms in the Priesthood of Art by Laurie MacManus]

That this harmful rhetoric made its way into Clara’s diary is no surprise. In fact, it’s irrefutable proof of the inner struggle women composers have faced throughout history. Clara demonstrates how the sexist messages affected them deeply and inhibited their work.

Perhaps Clara’s belief on the subject of women composers should be summed up as confusion—confusion that society preached she should not be capable of what she innately desired.

And so, my plea for the future—when we speak of Clara Schumann the composer, may the line we quote of hers not be one of self-doubt but rather, one of irrepressible desire:

Clara Schumann

Sarah Fritz is a professional musician and writer, working on a book about Clara Schumann.

She has an M.M. from the Eastman School of Music and is on the faculty of the Westminster Conservatory at Rider University.

You can find her on Twitter @sarahfritzwritr or her website.

I wonder if bearing eight children and the societal patriarchal feeling was that women are better being mothers and wives greatly influenced her thoughts about living beyond what was considered her rightful place.

Having ‘work or a career’ ‘ beyond the home for those women who had no need to go into domestic service and of a certain class was possibly seen as being ‘common ‘ and vulgar.

Consider the fate of Mozart’s sister who in the end retired to a convent.

Did I read she composed as well as being a skilled pianist but her father and society forbade any career for her?